As I

quoted back here, on 14 Nov 1771 the

Massachusetts Spy published an essay signed “Mucius Scævola” that called Gov.

Thomas Hutchinson a “USURPER,” which was at least close to sedition. After some effort, the governor convinced his

Council to respond to that essay.

That body didn’t summon just

Isaiah Thomas, the newspaper’s printer. They also sent a message to

Joseph Greenleaf, who in January had put his “30 Acres of choice Land” and “handsome Dwelling-House” in

Abington up for sale and moved into Boston—to devote more time to the press.

That was an extraordinary action for an eighteenth-century gentleman. British society had an established social ladder. Journeymen aspired to become independent craftsmen with prosperous workshops, no longer managed by another man. Independent craftsmen aspired to become merchants arranging lucrative ventures, no longer working with their hands. Merchants aspired to become landed gentlemen overseeing large farms, no longer subject to the vagaries of trade because their fortune was now in “real estate.”

Furthermore, British society still considered

printing a craft, not a gentleman’s profession. Printers literally got their hands dirty, after all. Even writing for publication was less than genteel. Most upper-class authors published anonymously or under pseudonyms, though their neighbors and rivals often knew the real identities behind those pen names. All told, giving up a rural estate in order to go into publishing looked like a step or two down the social ladder.

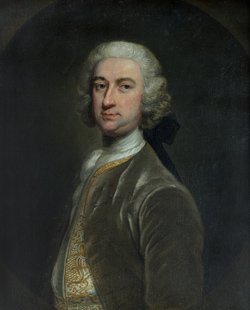

When 1770 began, Greenleaf was a country squire—a big man in Abington. He was a justice of the peace for Plymouth County. His had married Abigail Paine, older sister of

Robert Treat Paine, thus allying him with some other genteel families in southeastern Massachusetts.

But Greenleaf got excited about Massachusetts’s resistance to

Parliament’s new policies. He drafted sixteen resolutions that his town adopted two weeks after the

Boston Massacre, laying out a political philosophy that started with “a state of nature” and went on to reject any new taxes “passed in either of the Parliaments of

France,

Spain, or England” as

“a mere nullity”—a striking way of saying that the legislature in London had no authority over the people of Massachusetts.

Abington’s resolutions were published widely. The

Essex Gazette ran a letter from

New York that said:

The Resolves of those illustrious, and immortal Friends to the RIGHTS OF MEN—The Abington Resolves, have given their Brethren here, INFINITE PLEASURE, and I imagine some others as much Pain.

The same paper also ran a letter from London:

The Abington Resolves are too flaming and rash. They are rather like the transient flashes of passion, than the cool, steady, equal flame of patriotism and liberty…

Either way, Greenleaf seems to have been hooked on imperial political debate. Abington became too small for him.

In 1771, as I said, Greenleaf moved into Boston. What’s more, he made some sort of deal with Isaiah Thomas, the young printer of the

Massachusetts Spy. It’s not clear what their arrangement was because the culture of the time didn’t have the occupational category of “publisher”—i.e., someone who finances and manages the printing and selling of a periodical or books without actually operating the press.

The Council stated in December that Greenleaf “was generally reputed to be concerned with Isaiah Thomas, in printing and publishing a News-Paper, called the Massachusett’s Spy.” The following year, the

Censor magazine,

set up to support the royal government, said Greenleaf was “reputed…to be in Co-Partnership with Mr. Thomas.”

In October 1772, Greenleaf himself advertised that he “carries on the Printing Business with

E. Russell.” But that was a footnote to an announcement that he had opened “A STORE, INTELLIGENCE-OFFICE, and VENDUE ROOM,” or auction house, selling imported goods, cloth, “Bristol Beer,” and more. He was presenting himself mainly as an import merchant, with the printing as a side business.

A lot of people then and since nonetheless referred to Greenleaf as a “printer.” I doubt he set type or worked the levers on the press (as demonstrated above by Gary Gregory of the

modern Edes & Gill Print Shop). But he definitely worked with Thomas to publish the

Spy and later the

Royal American Magazine, probably by putting up money and writing and editing copy. In between those ventures he also funded work in Russell’s shop (but not the

Censor, both the magazine and Greenleaf were anxious to assure people).

Because of his financial interest in the

Spy, Gov. Hutchinson and the Council summoned Greenleaf to discuss the “Mucius Scævola” essay. According to Greenleaf:

On the 15th of November last [i.e., in 1771] I received a polite message from the Governor and Council, by Mr. Baker, desiring my attendance at the Council Chamber, this I have no fault to find with: The distress of my family, on account of a sick child, who died that day, was such that I could not possibly attend, and I excused myself in the most polite manner I was capable of.

Indeed, the 18 November

Boston Evening-Post ran a death notice for “Mr. Joseph Greenleaf, jun, in the 18th Year of his Age, Son of Joseph Greenleaf, Esq.”

But Gov. Hutchinson wasn’t satisfied with Greenleaf’s excuse for not coming to the Council chamber. Because he didn’t think the man was simply Thomas’s partner in putting out the

Spy. He believed that Greenleaf was “Mucius Scævola.”

TOMORROW: Greenleaf’s claims.